The Enemy (Part 2)

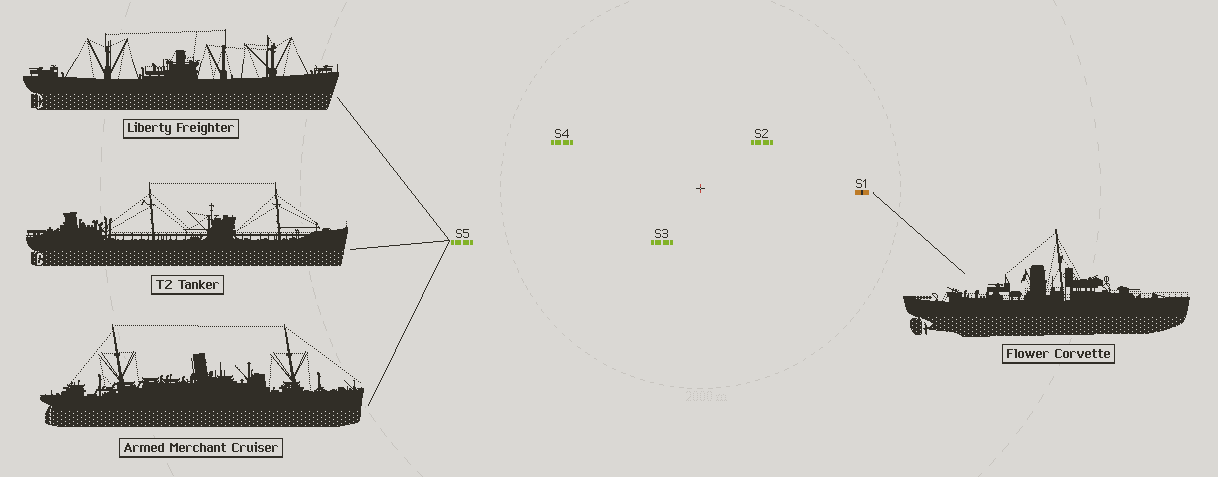

Based on research on WW2 convoys, I moved on to coding. First an algorithm that spawns convoys with a realistic structure, and populates the stations with ships rolled from a pool of basic classes.

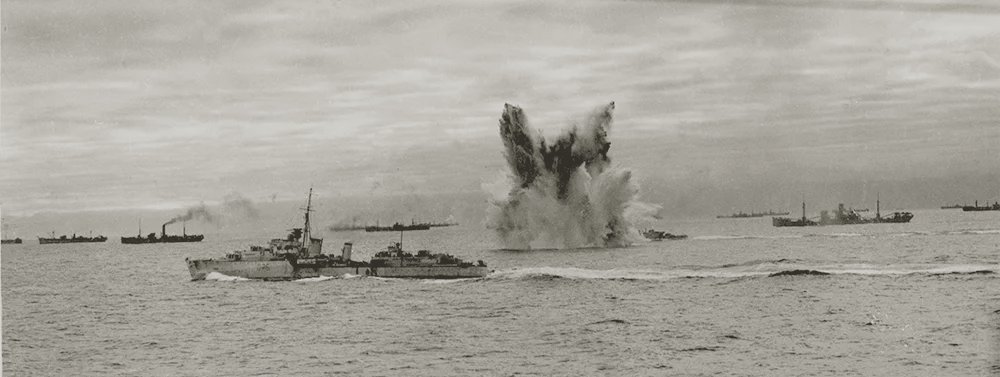

A small convoy at sunrise

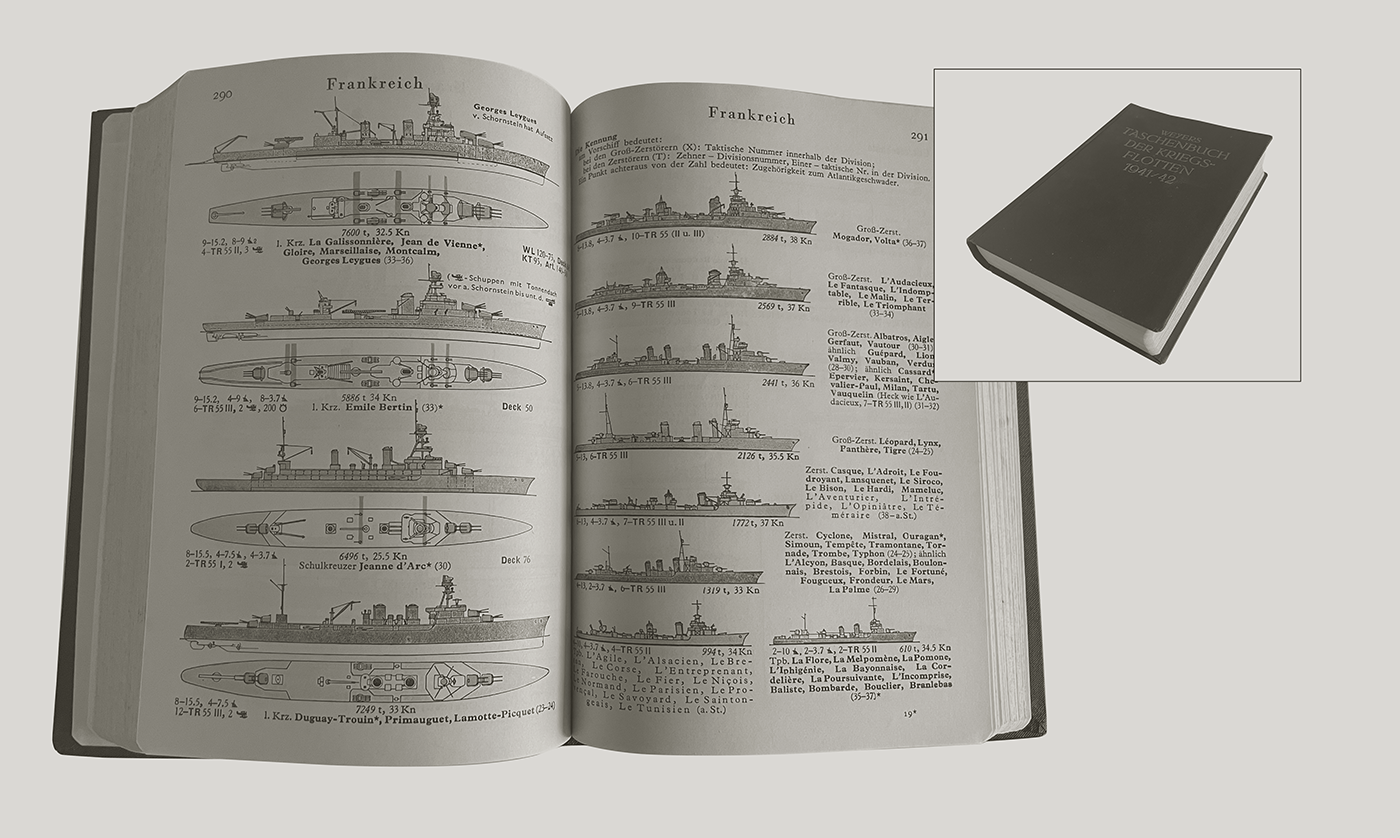

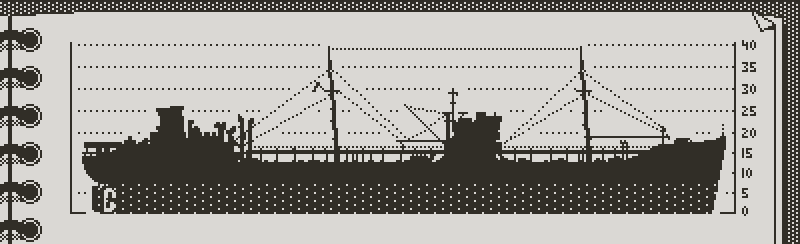

On this, let me tell you something: I love the research, but I don’t envy the job of historians who attempted to compile the hundreds of classes of ships and variants that played a role in the Battle of the Atlantic. I naively hoped to come up with a manageable selection of all the most common types of ships, both civilian and military, that sailed from the North sea down to the Caribbean. And then pick a couple of the most iconic classes per type.

But between steam merchants, motor merchants, many classes of freighters, armed merchant cruisers, tankers, whalers, ocean liners, troop transports, landing crafts, minesweepers, trawlers, sloops, corvettes, frigates, destroyers, destroyer escorts, light cruisers, carriers, escort carriers, battlecruisers, battleships, you’re counting hundreds of classes, which all played a part. And many of these classes have variants and conversions, increasing the number to thousands.

When it comes to ships, this recognition book shows the depth of the rabbit hole

Making sense of this is a pharaonic task, and the couple of weeks I spent reading about the subject left me certain of one thing: a lifetime wouldn’t be enough. Even highly regarded films and literature, with access to renowned consultants, don’t get all the facts rights. And there’s not only the question of what ships to feature, but the challenge of understanding their roles, and have them operate in the game accordingly.

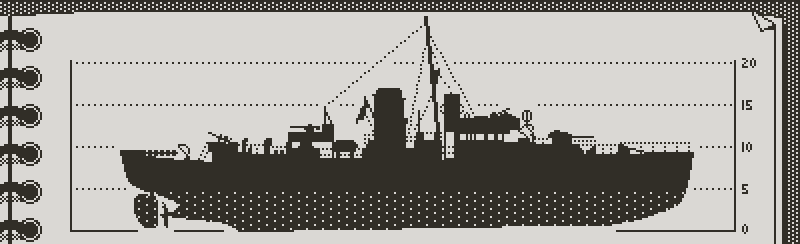

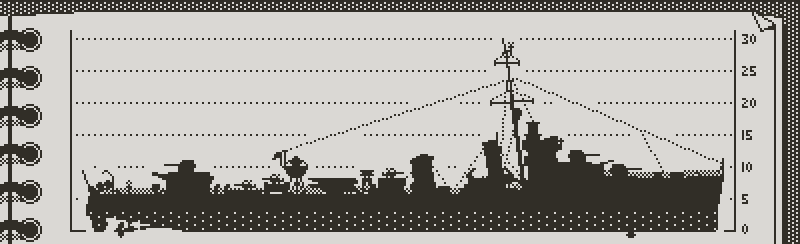

Black Swan class sloop

It’s not to say they’re aren’t a few famous ships that played an essential role. For instance the Liberty class, as the U.S workhorse freighter, built faster than the Germans could sink them. Or the Flower class corvette, which escorted almost every ally convoy. Or the Black Swan class sloop, which struck fear in the hearts of u-boat crews. One of them, the HMS Starling, commanded by the legendary Captain Johnnie Walker, directly sunk or participated in the sinking of 11 U-boats. That’s more than any other ship.

These will be featured in Atlantic ‘41, along with a few others too popular to ignore. In fact, these hero classes alone make for a huge pool. But like monsters in a rpg, more isn’t always better. There’s a sweet spot to find. Too few, and the game lacks variety. Too many, and their identity is drowned in the multitude. Like stats, past a certain number, it’s difficult to appreciate their impact on the game.

Johnny Johnson has excellent WW2 videos

This one is about the Flower class corvette

An iconic monster class is built around a couple of ideas. The skeleton is your bread and butter, low level class. The sorcerer is the spell caster glass canon. As the player encounters new monsters, they learn how to deal with them. But what’s the point in having bandits, pirates, scoundrels, thugs and brigands, when one can barely distinct them from their parent class, the thief? They muddy the original class, and only bring false variety.

Flower class corvette in Atlantic ’41

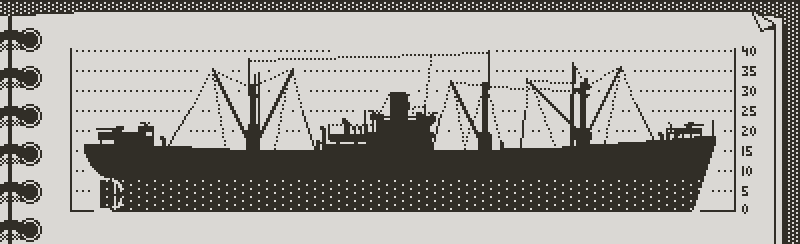

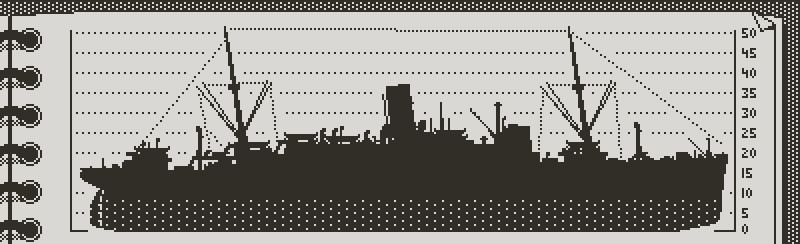

I took a similar approach for ships. The Liberty class is the bread and butter large freighter. Fairly slow, not too difficult to sink, but sometimes armed. The tanker is the defenseless, high tonnage target. The River class frigate is the late war U-boat terror. That method helped me to building a list of ships that offers enough variation to support the whole game, but also gives each class a unique role that the player can learn and remember.

Liberty freighter in Atlantic ’41

It’s still a complex task, in particular when taking into account the dates at which certain classes were commissioned and launched. Add to that the specificity of the different navies, and even with the ‘simple and iconic’ rule in mind, it’s a daunting prospect. I don’t have the final list yet (which I’ll keep secret as to avoid spoiling the game), but at this point of development I only need at least one class per ship type to cover all the main roles inside a typical convoy.

I already went over them last time, but here’s a quick reminder, along with their function in the game:

- Freighters: typical cargo ships. Average speed targets, varying greatly in tonnage. Sometimes armed with deck guns. They make for the bulk of ships sailing the Atlantic.

- Tankers: high tonnage, slow, defenseless targets.

T2 Tanker in Atlantic ’41

- Troops and passenger transports: high tonnage, high risk preys, in the sense that they can be of great importance to allies when carrying soldiers, but it’s forbidden to attack them when they transport civilians. I’ll explain the scoring system and the dBu standing orders in the future.

- Light escorts warships: corvettes, sloops, and ASW trawlers. Small but dangerous escort ships, in particular to submerged U-boats.

Admiralty V & W class destroyer in Atlantic ’41

- Heavy escort warships: fleet destroyers and destroyer escorts / frigates. Fast, well armed, and versatile. An open gunfight with them is a guaranteed trip to Valhalla, but they’re less competent at hunting underwater targets. Destroyer escorts and frigates are more maneuverable and better equipped for anti submarine warfare.

- Unique ships: aircraft carriers, escort carriers, battleships, battlecruisers, and large ocean liners. The hardest to find, hardest to kill, but most valuable prizes.

Armed merchant cruiser in Atlantic ’41

Within each role, I have several classes with clear, specific identities. For instance in the light escort class, the Flower class corvette is the most common encounter, while the Swan class sloop acts as “elite” unit. Both are more effective against submerged targets. Heavy escorts play an opposite role; they are deadly on the surface, but submerged, you have a better chance to evade them. This makes sense historically; destroyers were not seen as U-boat hunters. Consequently, ASDIC operators didn’t receive the same level of training as on smaller ships like corvettes and trawlers. Later in the war, destroyer escorts and frigates take on the role of elite U-boat hunters, and become the backbone of hunter-killer groups.

River class frigate

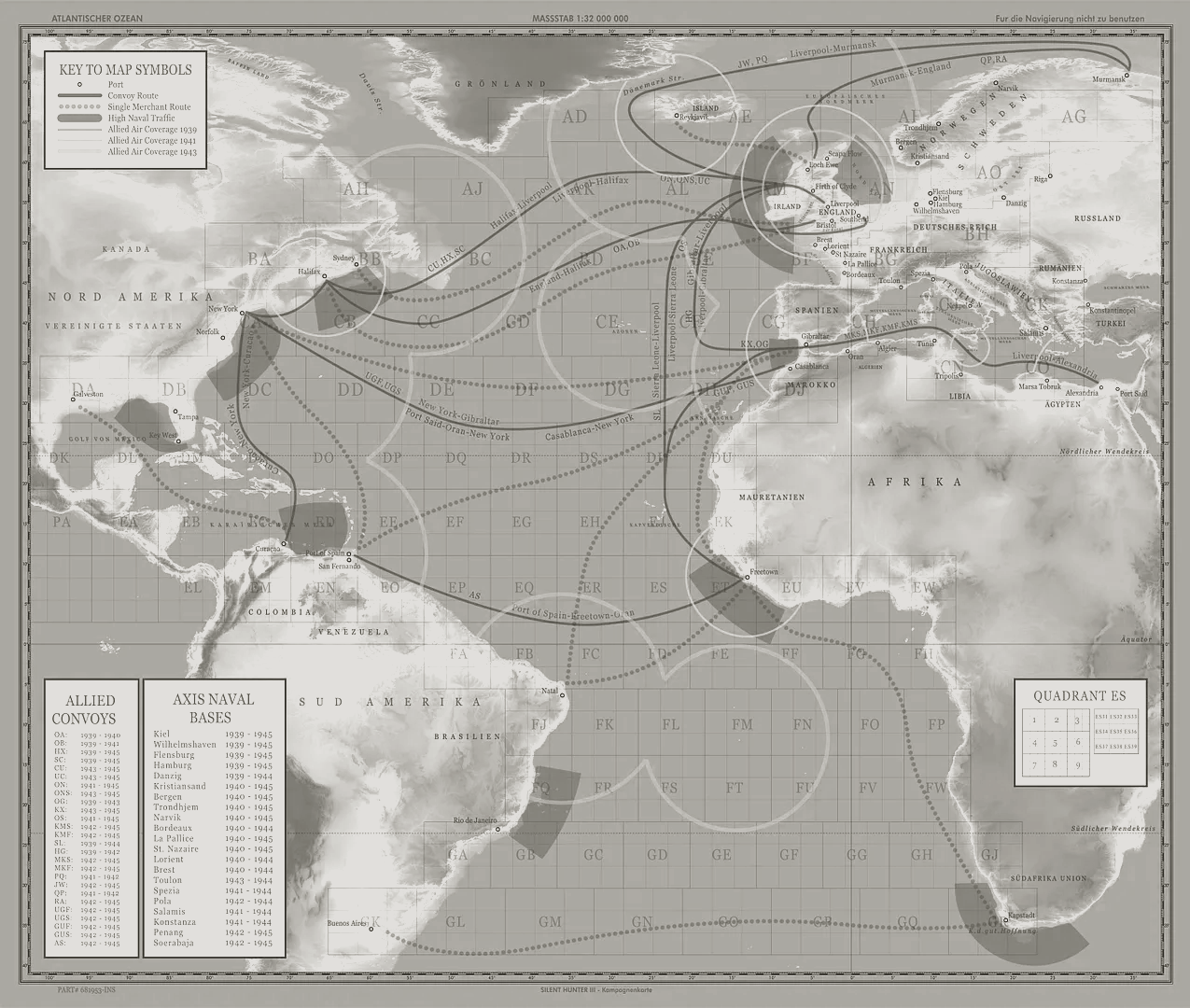

But deciding which classes to feature is only the first layer of the problem. In the future I’ll discuss how ships are spawned into the world map, whether they are part of a convoy or unescorted, and how this all relates to historical convoy routes and the complex power shifts that defined the Battle of the Atlantic. In all honesty my ideas for simulating the world and managing patrol navigation aren’t solidified. This is all pretty complex stuff, and I have a hard time figuring how feasible this is, both from a technical and gameplay standpoint.

Map of Atlantic convoy routes from Silent Hunter 3

I won’t be able to tackle that until after combat is implemented, so for testing I roll one of my pre defined convoys on an initial heading chosen at random. For now, I added an armed merchant cruiser, which can act as troop or passenger transport, a tanker, and a destroyer. That makes one ship for each type within regular convoys, which is enough to test AI related stuff.

Fight or Flight

Now to apply what I learned from convoys to the game’s AI. Obviously research didn’t make me an expert naval tactician. It’s the work of a lifetime. The goal is not to build a perfect historical simulation, but a simple set of high level rules describing a believable context, and offering a decent challenge. The game’s AI must find the simplest way to make ships act in a way that is consistent to convoy battles, while giving them enough individual agency to feel like autonomous entities.

All ships must obey to the orders of their convoy leader (convoy Commodore for the civilian ships, and escort Commander for warships). The game assumes that there’s always a leader for each group. If the leader is incapacitated, another ship takes over his duties.

A small convoy in Atlantic ’41. Green ships can be freighters, tankers, or troop transports. Orange ships are light escort ships

The convoy has two states: “normal”, and “alarmed”. The leaders give instructions specific to the state of the convoy. The convoy goes in alarmed state if the U-boat is detected, or a torpedo is spotted, or a ship is hit by a torpedo (or a dud, in some cases). In other words, for any tell tale sign of the presence of the U-boat. The convoy has 50% chance to go back to normal after a number of turns (undetermined for now, until I can play test) has passed without any new sign of the U-boat, or if it is convinced of its destruction (I’ll come back to this in a future log). The chance goes up by 10% for every subsequent turn without alert.

The first group is comprised of the escorted ships, often defenseless.

In terms of their AI code, they have two needs:

. Avoiding damage / getting sunk.

. Obeying the Commodore’s orders.

Since they are without weapons nor detection devices, they’re left with two actions: sailing, and keeping watch.

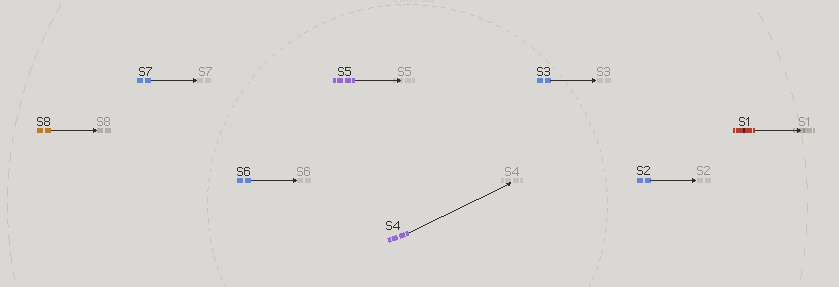

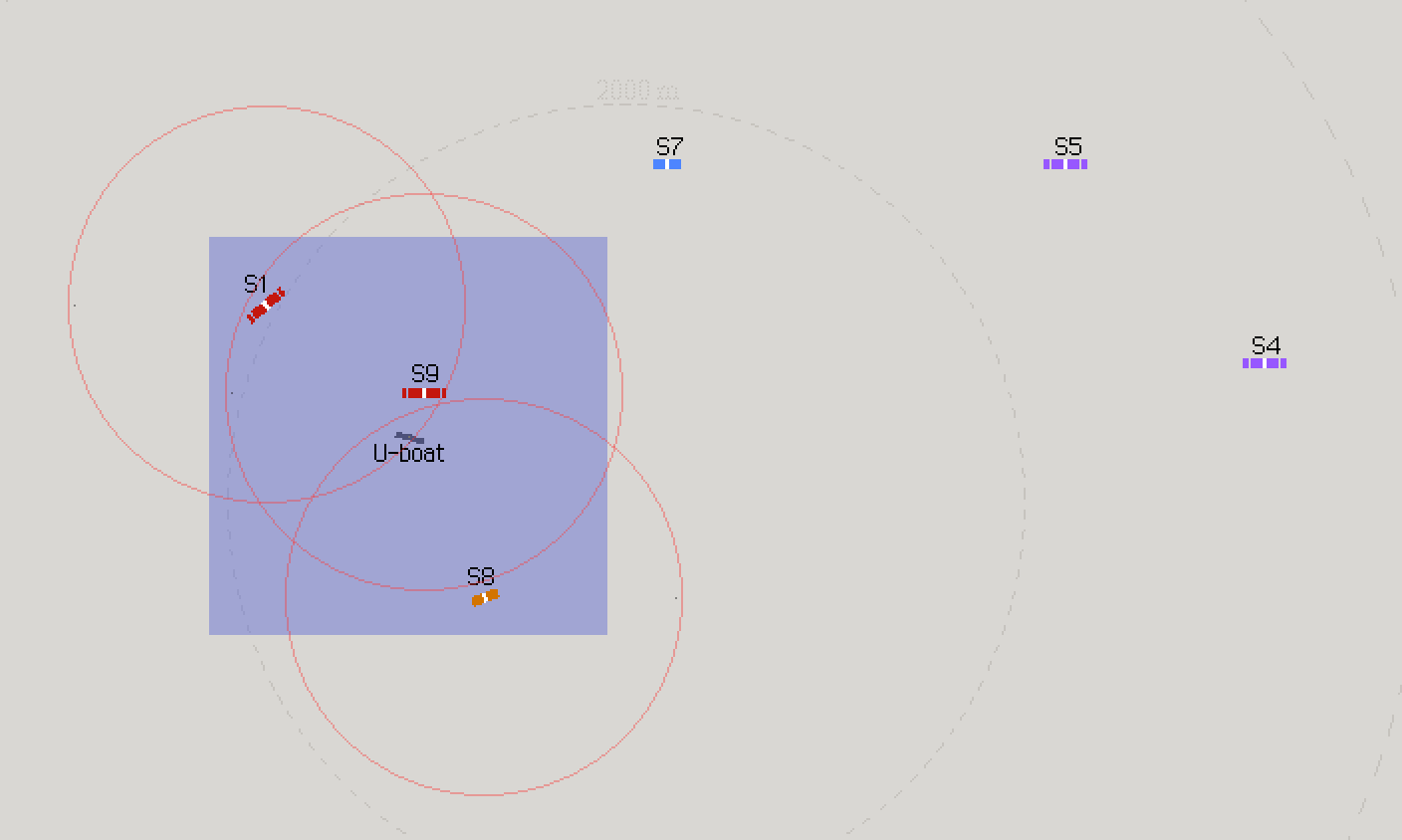

The largest convoy in Atlantic ’41. Red: heavy escorts. Orange: light escorts. Blue: freighters. Grey: tankers. Purple: troop transports

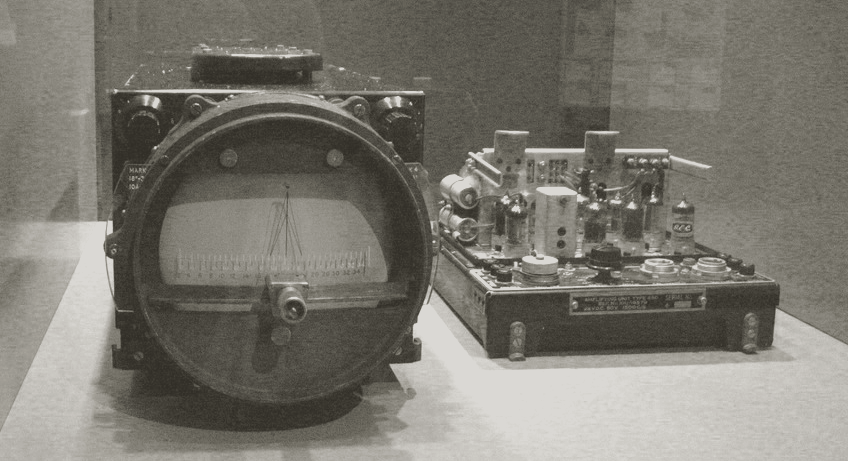

The second group includes warships. They’re armed, and possess sophisticated detection devices, like hydrophones and ASDIC. Their military duty places orders at the top of their needs, which trump even their survival instinct. They can sail, listen underwater, watch, and attack (either with guns, depth charges, or other anti submarine weapons).

Freighter S4 is late. She can sail faster than the rest of the convoy to catch up to her station’s position. During that time, she’s not bound to the convoy’s heading

When the convoy is in normal state, civilian ships and escort ships have similar orders. The Commodore sets the heading, and the speed of the convoy (1/3 of the maximum speed of the slowest ship). He can randomly order the convoy to zig-zag for a while. In this condition, ships don’t have any needs other than remaining within 300 m of their station, and following the convoy’s orders.

If they trail behind, they need to catch up to the convoy by any means, and can ignore the convoy’s speed, heading, and zig-zag orders. When in position, they fall back to convoy speed and heading.

All ships must maintain a watch at all times, and signal any threat to theirs leader, who will call the alarm.

An aerial photo shows the neat convoy structure

In alarmed condition, each group has specific orders.

The convoy maintains its heading, but accelerates to the full speed of the slowest undamaged ship. Stragglers, like wounded buffalos, are left behind at the mercy of U-boats, because the convoy’s safety prevails. It’s up to the warships to try and protect them until rescue ships can pick up survivors.

They act in a similar way as in normal condition, trying to keep up with their position inside the convoy. The difference lies with zig-zagging. If the U-boat position is known, they’re more likely to zig-zag with proximity to the threat. If they’re far enough, they’ll attempt to get away as fast as possible.

The Arctic Convoy

Over the past few years, there’s been a new wave of decent Scandinavian and Europeans WW2 films (“Narvik”, “Wil”, and “The Zone of Interest” come to mind). I didn’t find “The Arctic Convoy” to be very good, but it gave me an idea. It focuses on one of the 35 ships of arctic convoy PQ 17, which left Iceland on 27 June 1942 to deliver cargo to the Russian Front. The convoy lost its escort and was ordered to scatter, leaving merchant ships to choose their own course. Without spoiling it, the film explores the difficulty, for a civilian captain, to maintaining order under combat pressure.

Tribal class destroyer HMS Eskimo on arctic convoy duty

So I thought, what if civilian ships had a small chance of going rogue and ignoring the convoy instructions, out of inexperience or panic? That would be a nice way to throw the player off, because even with a few variations, there’s always the risk for the AI of becoming too predictable. Without going into all the details, it goes like this:

Any non warship has a small chance of going rogue. It acts on its own, ignoring the convoy. If the U-boat’s position is known, a rogue ship sails directly away from the threat. In rare cases, it can pick a random heading, like when the U-boat’s position is unknown. After a while, there’s a chance that the rogue captain goes back to his senses, and folds back into the convoy. But if that doesn’t happen, he will keep sailing his own course, even if the convoy goes back to normal.

PQ17 arctic convoy

That should do it for civilian ships. They had limited options anyway, other than fleeing and sticking to the convoy, so that makes for a simple behavior.

Bend Reality. Don’t Break It.

Warships work differently. As soon as the convoy is under alarm, the warships are on the move. They need to locate and sink the threat, keep it under, or drive it away. The easiest way to program that behavior would be to have the game cheat; roll under a number, and the warships magically roam around the U-boat’s location, dropping charges with uncanny accuracy.

This kind of shortcut is almost always easy to spot by the player. Even when the system doesn’t actively cheat, it tends to become predictable. This has two adverse effects; first the player can see through the tricks and take advantage of them. Second, giving AI controlled units more information than what they should logically have access to hurts immersion and believability. The world takes an artificial taste, where reality can break at the will of the game’s needs.

Silent Hunter 3, with the Grey Wolves expansion, does a great job with ship’s AI

Now, in all fairness, there’s no getting away from a certain level of simplification of the world. Simulating the realistic thinking of a Navy captain with years of battle experience couldn’t even be done on a high end PC by expert AI software engineers. Besides, even that wouldn’t be enough to calculate the behavior of an escort ship, subject to countless other factors like detection systems limitations, operator’s skill level, visibility, sea conditions, ambient noise etc.

Truth is, escort ships had very little way to know if a U-boat shadowed them. As we’ve seen with the way convoys were structured, the escort formed a large net around their flock, close enough from one another so that their ASDIC ranges overlapped. That didn’t guarantee the safety of the convoy from a skilled U-boat captain, who waited for the moment to strike right outside the range of detection. The boldest even slipped through the cracks at slow speed deep below the surface.

ASDIC system, circa 1944

In many cases, the allies had to suffer a few losses in order to get a sense of the general location of the threat, based on optimal torpedo firing distance and spatial distribution of the victims. That morbid triangulation trick gave them a more manageable search area. They combed the zone with a meticulous grid pattern, hoping that one of them got close enough for the ASDIC to pick something. In doubt, they filled the ocean with enough depth charges for a lucky hit, or to scare the U-boat away from the convoy.

This brute force technique required many coordinated ships and a lot of time. It wasn’t unusual for U-boats to be depth charged for 12 hours straight, driving them at the limit of their battery charge or air supply

In the film Greyhound, a convoy struggles against a well organized Wolfpack

This poses a problem for the game; as much as I like the idea of the suspense of a long depth charge run, there’s a point at which tension could turn into boredom. This is particularly true for a game with fairly static and limited graphics inside the U-boat. The player doesn’t have the luxury to walk around the boat, or look at what’s going on through an exterior camera. Other than check the hydrophone (which is not implemented yet) for escort ships movements, not much else to do than activating the “next turn” command.

I made the choice of limiting the game’s art to the crew’s perspective

I think that the game needs a system that helps move things forward without falling into the trap of teleported ships or omniscient enemies. Accounts of battles between U-boats and escort ships demonstrate that, short of random luck, chances of cornering and killing the U-boat came down to its activity.

The more the boat attacked, the more it spent time with its periscope up, the faster it moved to get into a favorable position, the more it risked giving up itself up. When that happened, the engagement shifted in favor of the defenders. With enough ships, they were able to swarm the area and prevent the U-boat from reaching periscope depth. Blind and unable to attack, the only hope for the submarine was to vacate the area at a crawling 7 knots, while praying for the hunters not to pick up the scent again.

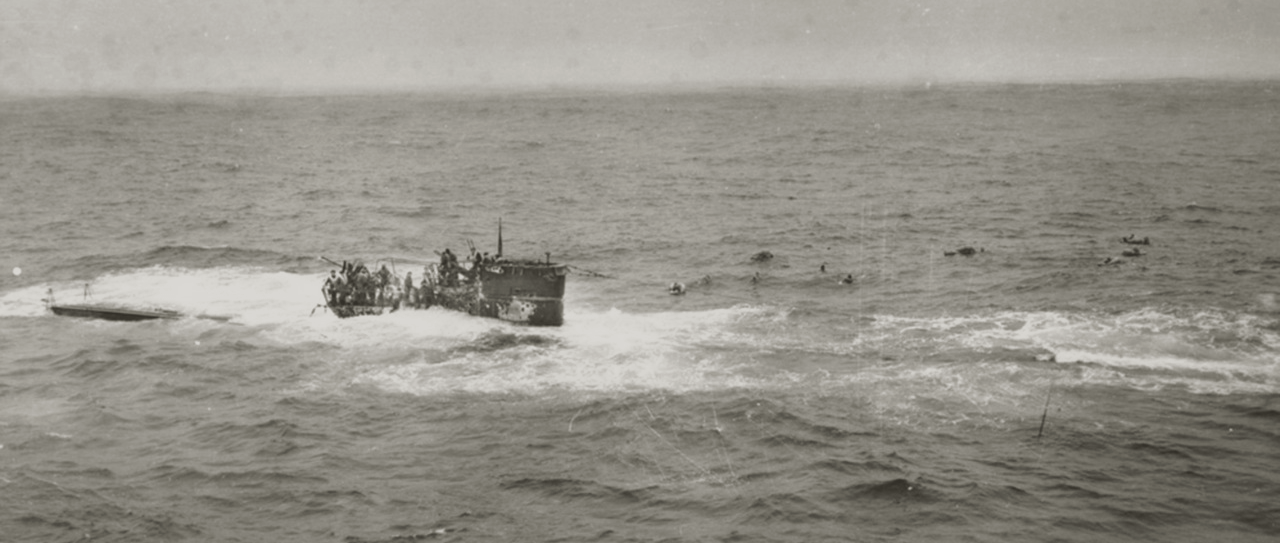

If brought to the surface, the U-boat was done

Here, U-505 is captured on 4 June 1944

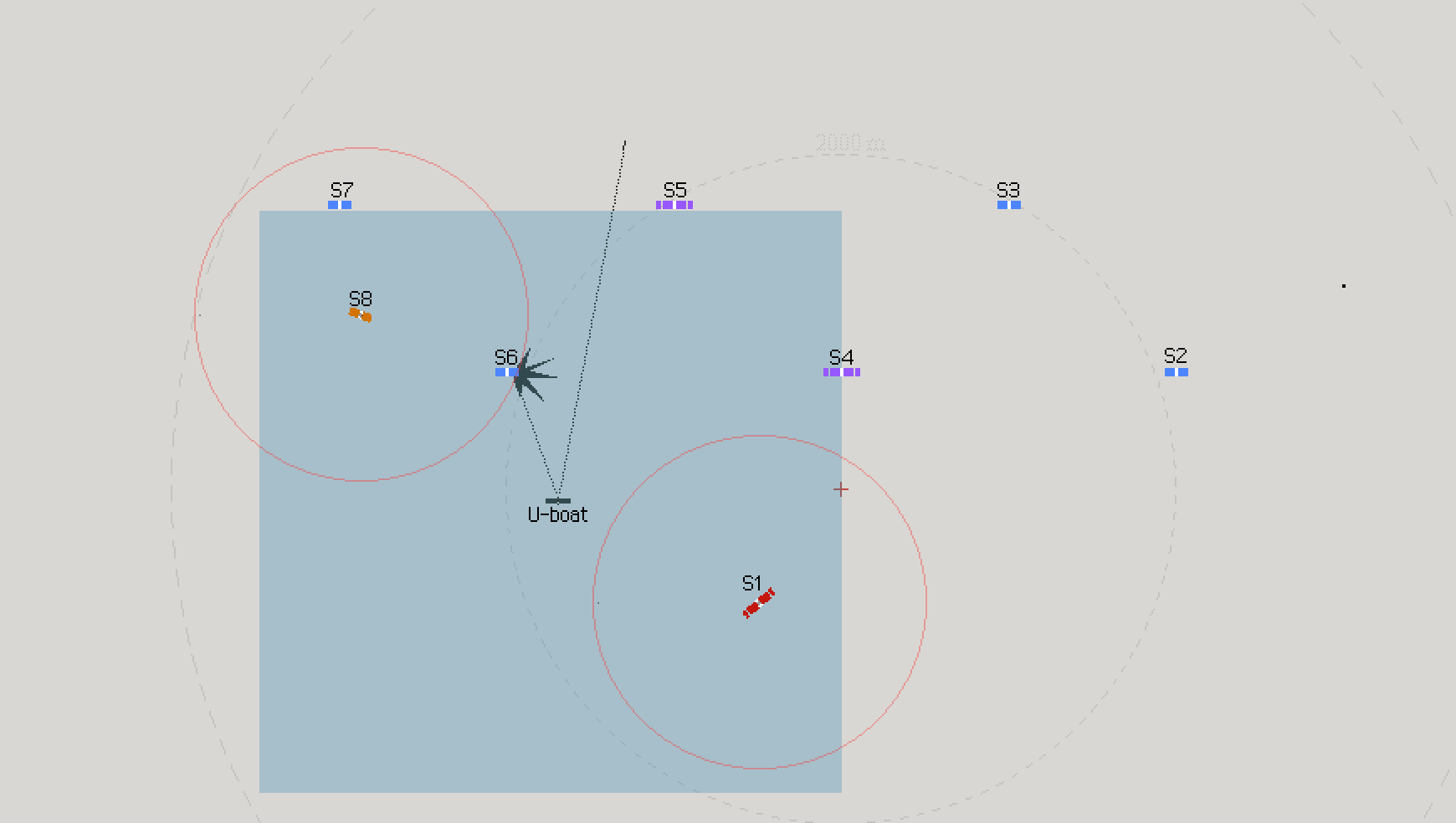

I thought of a system that could simulate the idea of bread crumbs left by the U-boat’s activity; in other words, a simple way to convey escort ships using deduction and experience to get a general sense of where to conduct their search. It revolves around the idea of a search zone centered around the U-boat.

With the boat hidden and the convoy in normal mode, escort ships remain at their assigned convoy stations. At the first indirect sign of the boat, like a torpedo hitting a ship or being spotted, the search area spawns. It’s a vast square, 4000 m wide. Its large size suggests that the escorts have a vague idea that a U-boat is operating in that sector, which they can deduct from the direction from which the torpedo came, or which side it hit its target (in reality, torpedoes did not always need to physically hit the hull. The could glide under the keel, where the magnetic pistol would trigger the detonation).

The U-boat hit S6 and missed S5, which spotted the torpedo.

The blue square shows the resulting search area.

Escort ships S1 and S8 begin the search. Orange circles show their ASDIC ranges

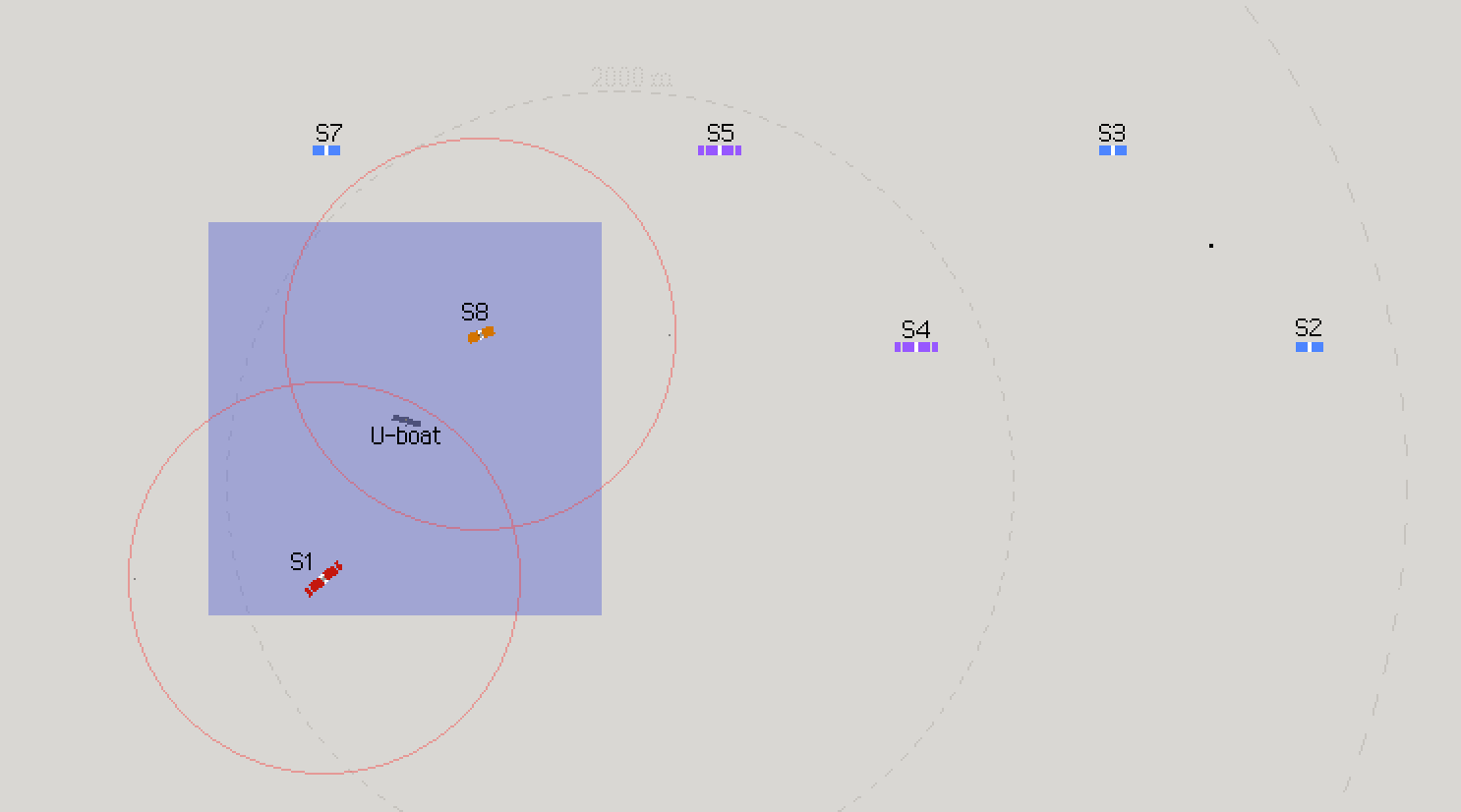

In subsequent turns, with each new target hit, or torpedo spotted, the search zone shrinks around the U-boat, simulating the deduction work done by escort ships, as the U-boat conceded more hints. It is recalculated each turn with new targets being hits or the U-boat being detected, for as long as the convoy is in “alarmed” condition.

Several hits during the same turn don’t stack but count as just one hint. The idea being that captains often tried to attack multiple targets at once and displace quickly, rather than space out torpedoes and give the escort more time to detect them. My hope is to create a risk/reward system encouraging realistic tactics.

A few turns later, the area has shrunk, after one escort ships got a partial localization

The bold player will try and get in the best possible position for an all out attack. The cautious one will attack once and disappear, giving little to work with to the escort, only to then patiently shadow the convoy for a new opportunity. But like in real life, re engaging the enemy too soon, with escorts roaming around, only increases the pressure.

Every turn, the search zone is updated, shrinking or growing at rates depending on the U-boat’s behavior. The values will need extensive play testing but so far I have the following:

. If a ship hears/spots the U-boat, the global search zone immediately shrinks to 1000 m x 1000 m.

. With every torpedo spotted, the zone shrinks by 1000 m.

. With every new ship hit by a torpedo, the zone shrinks by 500 m.

. Every turn spent without the U-boat giving any hint of its location, the zone grows by 500 m, simulating the trail going cold.

One more destroyer makes very difficult for the U-boat to stay out of ASDIC range

The zone can’t get smaller than 500 m x 500 m, taking into account that even ASDIC couldn’t pin point the location of a U-boat with perfect accuracy. And even a small zone doesn’t mean that the U-boat will be hit by depth charges. Escort ships have a kill box, for now set at 250 m x 250m . Inside that area, and if they feel like it’s worth dropping charges, a hit is rolled, taking into account the effective proximity to the boat (dropping directly above the target has much higher chances) and its depth. Changing depth, or diving very deep, grants a bonus to evading depth charges.

Since escort ships distribute themselves evenly inside the search zone, convoys with numerous escort vessels are more prone to kill the U-boat. Next time, I’ll cover detection and hit rolls, and all the various tricks the U-boat can use to shake off its tail.

Shadowing a convoy

Like mentioned in the beginning, I only have a partial implementation of the enemy’s AI, in particular when it comes to detection and attack. For instance, a U-boat detected on the surface will be fired on, or even rammed if close enough to an enemy. I’m also working at a visual and audio representation of depth charge attacks from inside the U-boat, which is an interesting challenge, considering self imposed limitations; if you’ve been following these logs from some time, I explained how the player’s perspective is always limited to first person, without ever showing the action from the outside.

Convoy tagged in the tactical chart

Still, I’m getting close to having a full playable combat in crude form, with the player and AI taking successive turns. It’s going to be a decisive moment, which hopefully will work well enough that I don’t have to reconsider fundamental choices made up to this point. But we’ll know soon enough.

More soon.

Atlantic '41

A WW2 U-boat Simulation for the Playdate

| Status | In development |

| Author | StephanRewind |

| Genre | Simulation |

| Tags | 1-bit, Pixel Art, Playdate, Turn-based Strategy, World War II |

More posts

- Upcoming log and Cranko! interview11 days ago

- Visual Upgrades55 days ago

- The Enemy (Part 1)Jul 15, 2025

- Los!May 29, 2025

- Preparing the FutureApr 07, 2025

- Project ResetApr 01, 2025

- Small BeginningsFeb 24, 2025

- Death by a Thousand ShellsDec 17, 2024

- Next devlog a bit delayedOct 13, 2024

Comments

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.

Such dedication, very impressive!! I'm still considering buying the hardware in order to play this game once it's done, because I truly feel like I'd be missing out on something amazing if I don't play it!

The only reason i am still keeping playdate! Great job as always Stephan!

Hopefully you won’t regret it :) Thank you for the continued support.

🙌 excellent

This is all just breathtaking stuff <3